By Nanci Hellmich - USA TODAY

July 22, 2014

Conflicts about retirement timing arise when one partner is forced to leave their job unexpectedly.

Two-career couples sometimes struggle with the best time to retire that will suit both of their needs. He may be ready to retire, but she loves her job and wants to keep working. She may think they need a bigger nest egg, but he feels they have enough saved and should enjoy some time together.

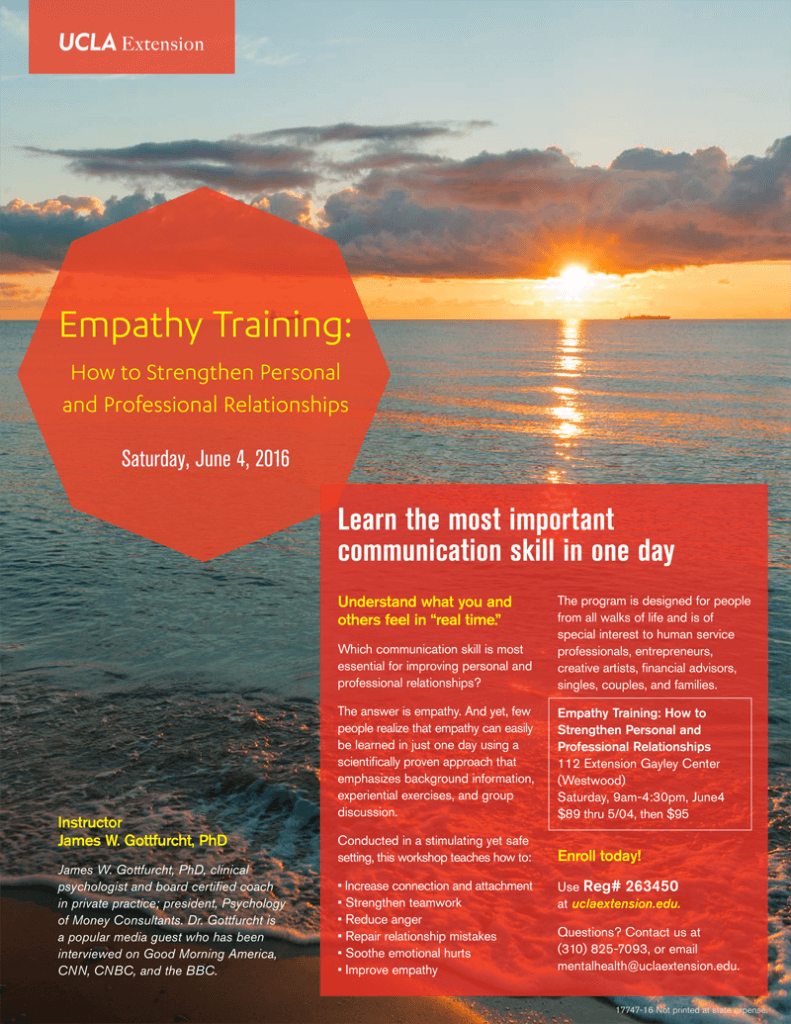

Los Angeles psychologist James Gottfurcht has worked with people facing this dilemma, including a couple in their mid-50s who came up with a clever resolution.

The husband wanted to retire after a successful career as a certified public accountant. He wanted to travel with his wife, their families and closest friends, but his wife wasn't ready to leave her job as an attorney. She had put her career on hold for 20 years while rearing their children, and she had just begun to build a successful practice that included being an international keynote speaker.

"They were locked in a power struggle with each feeling entitled to what they want. They were passively aggressively digging at each other," says Gottfurcht, president of Psychology of Money Consultants.

Gottfurcht had the two practice empathy training, taking turns talking about and listening to each other's needs, feelings, thoughts and aspirations, and they moved toward a more generous, caring and supportive attitude with each other.

They came up with a compromise: The husband agreed to embrace her career, and she agreed to take off six weeks a year to travel with him. They decided to spend some of the money from her income to hire a landscape architect to build a lovely garden with a stream and a waterfall so that he had a sanctuary to enjoy when he was home alone. "When they got to that compromise, they stopped bickering. They each felt more appreciative of the other and more loved than they did before," he says.

Money is often at the heart of any discussion on the timing of retirement.

Couples need to talk about how they envision their golden years and whether they have enough money to accomplish their goals, says Cyndi Hutchins, director of financial gerontology for Bank of America Merrill Lynch. "A good financial adviser can show a couple what the impact will be if they work just a little longer."

A survey commissioned by the company found that 42% of couples ages 50 and older have had in-depth discussions with their spouses about their net worth; 41% have discussed where they'll live; and 57% have talked about wills or inheritance plans.

If couples can come to some kind of agreement on activities or interests that they can pursue together, it can make retirement more enjoyable for both spouses, she says. For instance, when she was a financial adviser, Hutchins worked with a couple where the wife was retiring from a law firm and her husband was retiring from a utility company. They discussed what they would like to do and ended up opening a Christmas tree farm, which they've been running for 10 years, she says.

Most conflicts about retirement timing arise when one partner is forced to leave a job unexpectedly because of a firing, layoff or downsizing, and that partner wants the working partner to retire, too, says psychologist Robert Bornstein, co-author of How to Age in Place.

Couples who plan and discuss the timing of their retirement tend "to have a softer landing because they've had time to get used to the idea," he says.

But when someone loses a job unexpectedly "it's a shock for the person who is laid off that often spills over into the relationship," Bornstein says. The person who has been laid off may be ready to move near the grandkids, but the spouse had planned to work for another five to 10 years, and their identity is tied to their position, he says.

There are creative resolutions to these differences, Bornstein says. After one woman he knows lost her position, she started helping her husband for 10 to 20 hours a week, doing bookkeeping and other administrative work to take some pressure off of him. "It was a win-win" for both of them, he says.

Coming to an agreement on the timing of retirement requires communication, empathy and probably compromise, says Leslie Connor, a psychologist in private practice in Wilmington, Del. "In a compromise, everybody feels like they lose something because they did not get exactly what they wanted. Yet, there is the ultimate gain of staying together while meeting some of each person's needs."

It's important for both parties to speak up, she says. If you aren't ready to leave your job but do so because your spouse requested it, you may regret it, and "it's your job to prevent resentment. If you find yourself in a place where you are resenting someone else, that means you are not taking care of yourself," Connor says.

Joe Burgo, a psychologist in Chapel Hill, N.C., recommends that couples avoid the natural tendency to assign fault. "Compromise in long-term relationships means accepting that your needs won't always coincide, and you may both have to make sacrifices. Each of you can't always have everything that you want if you're to stay together."

Search for