By Nanci Hellmich - USA TODAY

June 22, 2014

Retirees often feel extra stress about money because of scarcity and not earning an income.

Couples are often at loggerheads on how to spend their money in retirement. She may may want to live it up a little, but he wants to pinch pennies so they don't run out of money.

For some couples, such disagreements are a long-standing problem in their relationship, and retirement adds extra stress because there is often a scarcity of money and anxiety over no longer earning an income, says Los Angeles psychologist James Gottfurcht, president of Psychology of Money Consultants.

In fact, 71% of U.S. adults report that money is a significant source of stress, according to an American Psychological Association survey.

Gottfurcht often works with couples who disagree about how to spend their retirement income. He recently helped a couple in their mid-60s who were preparing to retire. She liked to buy expensive jewelry and clothes. He wanted to travel and go to sporting events, plays and concerts.

"He was more conservative with spending, and she was more carefree. Her purchases added up to much more than his. The difference in spending had been a sore spot throughout their 32-year marriage," Gottfurcht says.

He worked with the couple to help the wife figure out that she enjoyed buying clothes and jewelry because her late mother had given her those things to express love. The wife was then able to realize her husband was burned out from working and had been carrying too much financial pressure because of her spending habits. She felt guilty and decided to cut back significantly, he says.

The husband proposed that they downsize and sell their home and move into a condo. They saw a certified financial planner and figured out their budget so she could continue to buy some of the things she enjoyed but not nearly as much as before.

New York-based attorney Ann-Margaret Carrozza says many retired couples have disagreements over money, no matter how much they have accumulated. "A lot of it goes back to how they grew up and whether they have the mind-set to enjoy themselves now or save the money for a rainy day."

Sometimes, people don't know when to "take their foot off the pedal and enjoy their lives. I have a multimillionaire client who won't buy an air conditioner for the house."

One of the biggest areas of disagreement: how much money they're going to give their financially strapped adult children, a problem many couples are experiencing given the "less-than-stellar economic recovery," Carrozza says

For instance, she worked with a retired couple in which the wife kept giving an adult son money, and finally, her husband had had it. They sat down with Carrozza and decided to set a limit on how much they give their son each year. Anything over that amount would be a loan with interest.

If their son did not pay back the loan before they died, then his inheritance would be reduced by that amount. "This helps prevent a battle between the children later on when we are administering the estate," she says.

Another couple Carrozza worked with were fighting over whether they should co-sign a student loan for their granddaughter's college education. The wife wanted to sign it, so they did. Then the granddaughter didn't finish college, and the loan has "negatively impacted their retirement quality of life," Carrozza says.

Couples have to come to terms with how much money they can part with "without leaving themselves strapped," she says. She encourages clients to give adult children "loans" rather than gifts, so if the child gets a divorce, the money would not be counted in a settlement as joint property.

St. Louis psychologist Diane Sanford advises couples to create a budget for six months of all their expenses, then see what they need to adjust to meet their budget and have the lifestyle they want, she says. The budget provides a neutral way of starting the conversation about spending.

When couples can't come to an agreement, they should see a financial adviser who can provide a "bright, shining light of objectivity" on the discussion, says Pepper Schwartz, a sociologist at the University of Washington in Seattle and a relationship expert for AARP. "Once they agree on a budget, they can figure out what they can afford."

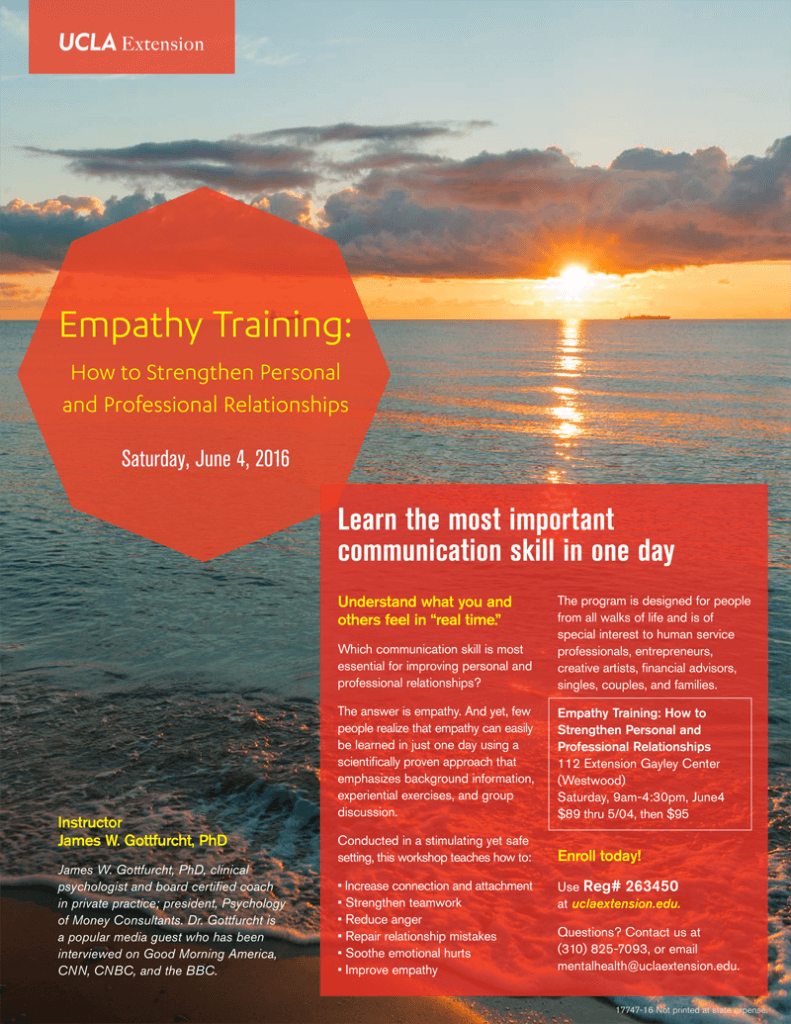

Gottfurcht has found that many couples benefit from empathy training, a brief program in which one partner talks about what he or she is thinking and feeling. There is no right or wrong, and the speaker's feelings are assumed to be valid.

The other partner listens, makes eye contact and takes in what the speaker is saying without interrupting, giving advice, asking questions or judging. Then that partner mirrors back what the speaker said, trying to capture the essence. The process is repeated until their speaker feels understood. And then they reverse roles.

This is especially important for planning and living in retirement, he says. Couples need to take turns talking about their aspirations and fears.

"This improves the understanding they have for each other, and they feel safer and more secure rather than argumentative," he says. "They give up their power struggle. This generally works with a wide range of problems."

Search for