By Terence Monmaney

In theory, the stock market works rationally and investors always exercise a disciplined calculus to part with their hard-won cash.

But in reality, as the previous two days have shown so dramatically, there is a lot of raw emotion and frail psychology in the “demand” half of the crowning equation of “supply and demand.”

The coupling of Monday’s 554-point drop and Tuesday’s 337-point rise in the Dow Jones industrial average “is an extreme example of the fact that Wall Street decision-making is based on emotional, not rational, analysis,” said Maurice Elvekrog, a psychologist and financial analyst in Bloomfield Hills, Mich.

He attributed the wild trading to “herd behavior” largely on the part of fund managers, who on Monday reacted en masse to a crisis in Far East markets by selling and then on Tuesday lapped up the now-discounted spoils. “Presumably the professional managers are doing their own thinking and analysis,” he said. “But they all tend to live in the same world and are very concerned about quarterly results. They don’t want to be left behind.”

It is only one of the oddities of “investment psychology” that professional money managers, with their high-flying financial credentials and reams of computer data at their fingertips, should be ignominiously compared to a bunch of skittish zebras fleeing a hungry lion.

Beyond herding, social scientists have documented or postulated other ways in which decidedly noneconomic emotions sway decisions to buy or sell stocks–including a paralyzing fear of loss, self-aggrandizement, wishful thinking and a sort of optimistic group-think.

No less an authority than the chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, acknowledged that there was more to market valuations than coldly assessed bottom lines when he said earlier this year that the stock market was subject to “irrational exuberance.”

Neil Weinstein, a Rutgers University psychologist specializing in decision-making theory, said that psychologists are making inroads into the “dismal science” of economics. “There’s continuing disagreement between one branch of economics, which treats people as rational decision-makers optimizing benefits to themselves, and the psychologists who point to biases and rationalizations” suggesting that investing behavior is not always optimal after all.

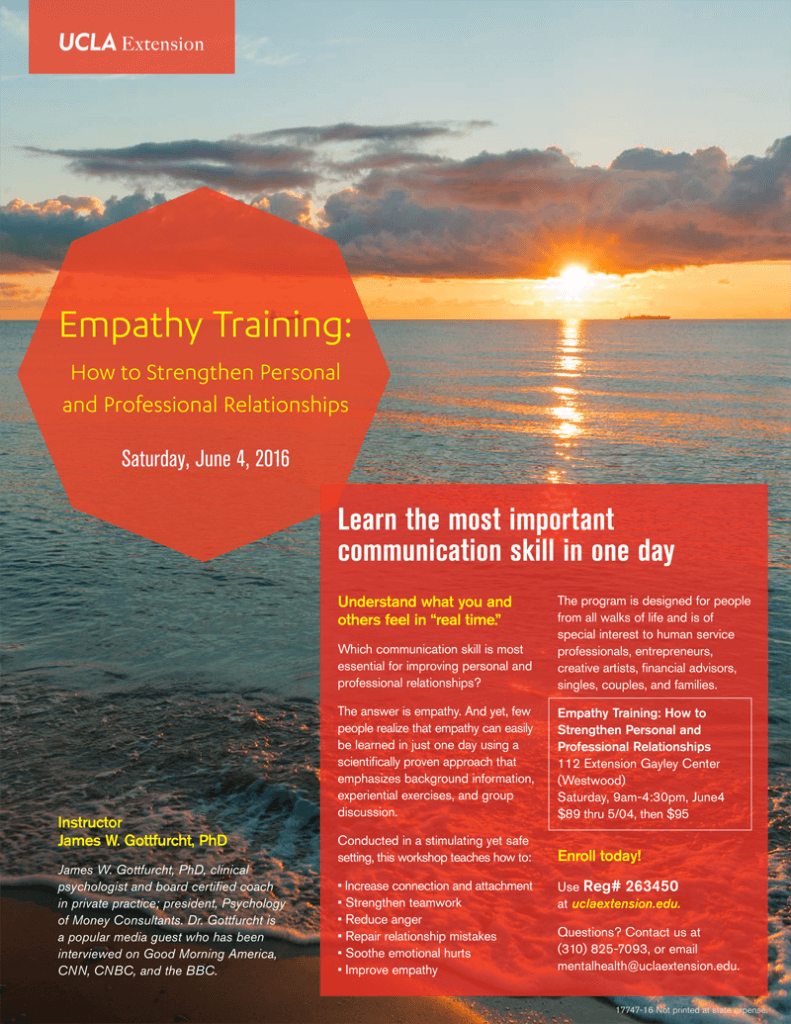

James Gottfurcht, a Brentwood psychologist who is a consultant to MasterCard on consumer behavior, speculates that the herd behavior that often drives buying and selling frenzies is human nature. He said it is a “survival instinct,” perhaps left over from humanity’s hunter-gatherer past. “The notion that there is safety in numbers is in our biology,” he said. “Even if you have a logical mind and a good investment counselor, you’re likely to be swept up in the group.”

Generally, researchers hesitate to label one person’s behavior “irrational” because it is hard to find agreement on what is “rational.” After all, one investor’s dog is another’s bargain.

But in evaluating investment behavior, researchers do have a mostly objective standard: the performance of a particular stock, stock index or market as a whole. And when investors sell a stock prematurely and miss out on substantial profit, or stubbornly hold on to a stock as it goes down the tubes, researchers consider that “irrational.”

A number of well-publicized studies have shown just that. A study by UC Davis finance professor Terrence Odean found that investors working with discount brokers, and thus presumably acting mostly on their own, tended to sell stocks that performed better than the ones that they went on to buy. Some of that is inexperience, researchers suggest, but it’s “irrational” to the extent that it reflects anxiety rather than calm analysis.

Another study, of shareholders in a large mutual fund, found that people acted contrary to the best financial advice and were eager to sell in a sinking market, rather than buying and getting a deal on shares. That, said Elvekrog, reflected what is perhaps the dominant emotion guiding investor decisions: fear of loss.

“People know they should be in stocks for long-term growth,” he said. “However, as they get closer to the moment of deciding what to do as the market heads down, the fear of losing overwhelms people and they run for cover and sell.”

Edward Charlesworth, a Houston psychologist and author of the 1994 book “Mind Over Money,” suggested that the globalization of the financial markets might make investors more anxious and thus prone to irrational behavior because decisions are now so much more complex, linked with foreign economies and currencies.

“So much of people’s reaction to money is emotional,” he said. “It’s not so much what happens to us and our money as what we tell ourselves will happen”–a phenomenon known to psychologists as catastrophisizing when the message is negative. And the less people know about how world markets function, he said, the more anxious they’ll be.

At the headquarters of the National Assn. of Investors Corp., an education group in Madison Heights, Mich., many members have called to express concern, but it has been nothing like the deluge during the crash of 1987, said Thomas E. O’Hara, chairman of the board.

He said that newer members of the group, which includes 700,000 individuals and 33,000 investment clubs, have fallen roughly into two groups: “The response of our newer members has been that this is scary. Older members have said, ‘Gee, this is the first time I’ve been able to find a bargain.’ ”

Perhaps the ultimate evidence that the markets are influenced by emotions and irrational ideas is the fact that you never know what is going to happen tomorrow, psychologists say. A purely scientific market would be drearily predictable; tomorrow’s Dow is anybody’s call.

Search for