By Ellen Tumposky

July 29, 2011, 12:39 AM

July 29, 2011 -- Lea Bowie, who retired this year and moved to Florida, gets scared and angry when she hears about the debt crisis.

"This thing is hanging over our heads like a sword," says Bowie, 67. "I'm terrified. I don't care who says what anymore. Just fix it!"

Bowie moved to West Palm Beach, Fla., from Brooklyn, N.Y., where she worked for 27 years in fundraising for the Polytechnic Institute of New York University, because her limited income goes further down South. She lives on fixed income from Social Security and her 401(k) and feels vulnerable to market losses and anxious about the threat to that Social Security check.

"It's my entire income," she says. "I have nothing else."

She feels Washington has let her and millions of others down.

"We voted for these people," she says. "We placed our trust in them. I paid my dues. I paid my taxes."

The emotions Bowie is confronting are widespread this weekend as the debt cliffhanger leaves millions of Americans wondering if the country is turning a corner to a less-solid future.

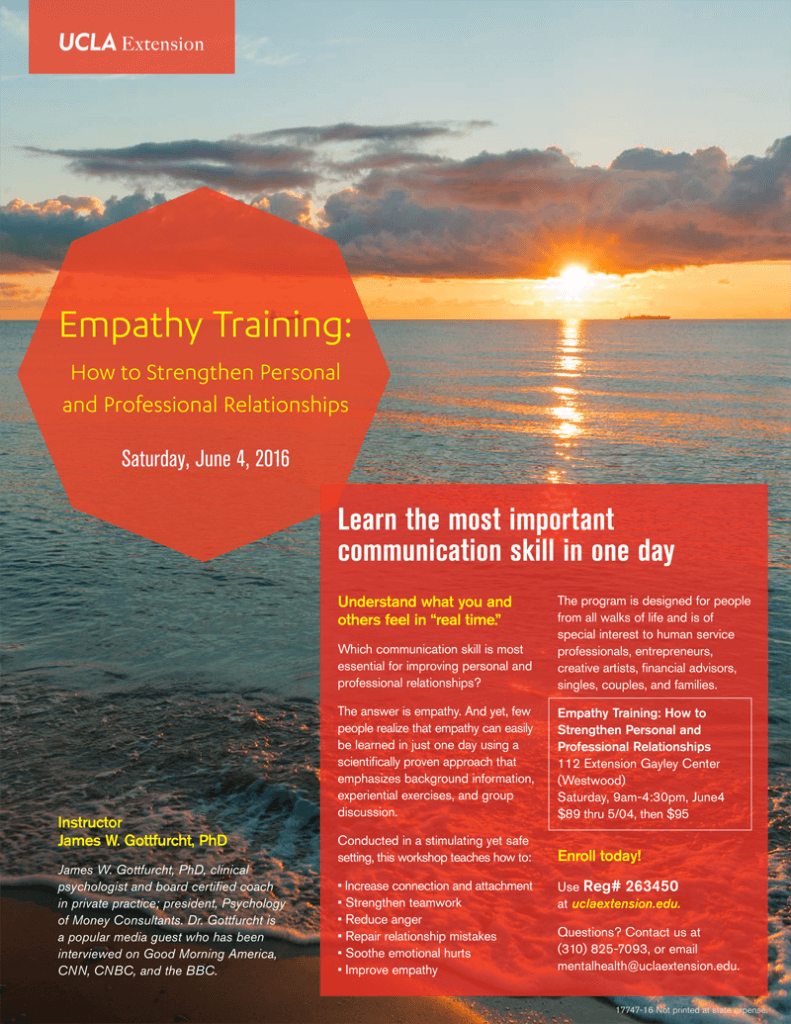

"A lot of stabilizing, rock-solid foundations are being threatened," says Dr. James Gottfurcht, a clinical psychologist and president of Psychology of Money Consultants in Los Angeles.

He compares the events in Washington to the reaction California residents have to an earthquake.

"The feeling that clients talk about when the earth is shaking, with terra firma crumbling -- this is like a financial tremor or earthquake," he says.

The crisis particularly affects people who have experienced financial stress in their growing-up years and deeply fear fiscal uncertainty, he adds. But ironically, the highly affluent can be more stressed than ordinary middle-class people because their self-esteem is tied to the health of their bank accounts.

Georgette Ryan, 44, from Nashua, N.H., is not among the highly affluent, but she is so stressed by the debt crisis that she has stopped watching the news.

"I was keeping myself up at night," says Ryan, who was laid off from her job in the New Hampshire juvenile probation office and then laid off again from a bartending job.

She is a single mom whose 23-year-old daughter -- a part-time bus monitor -- 13-year-old son and grandchild live with her. Ryan gets a disability check because she has fibromyalgia and also receives Medicaid.

"Everyday, I wonder about that," she says, because New Hampshire is cutting back.

She is dependent financially on her disability check but is actively seeking work.

"I don't like to mooch off the state," she says. "I'd rather support myself, but it's so tough out there."

When she tended bar on the day shift, Ryan says, "I'd serve more Coke and coffee during the day than I would alcohol," because a lot of elderly patrons came in to socialize.

"They worked hard all their lives and now their 401(k)s are getting threatened, their Medicare," she says. "I see firsthand how they struggle. It seems like the government is attacking the helpless."

Ryan worries about the direction the country is taking.

"Things are going downhill," she says. "It's scary for the future of our children. The U.S. is probably going to end up like a Third World country."

Congress and the White House, she feels, are letting citizens down.

"It's just a game of who's going to win," she says. "What should matter is the people win.

"It's the middle class and the poor, we always get stuck," says Bowie. "Every time they talk about this impasse, it makes me so nervous. I don't want to see doomsday coming. Let me know when it does, or doesn't."

Kathy Vitale, 60, a retired nurse in Bristol, Pa., is so anxious that she's upped her sleeping pill dosage even though her doctor told her not to get upset about politics.

Vitale has Crohn's disease and her daughter Jami, 36, has colitis. Both receive Social Security disability. Kathy Vitale's husband has a job with the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, but she says her $700 monthly disability check is crucial for paying the mortgage.

"If they stop my cash flow, we'll lose our home," she says.

She directs her anger towards House Speaker John Boehner, saying, "I want to take this man and have him live the way poor people live. He sees corporations; he doesn't see Kathy or Jami."

Americans are mad, says Gottfurcht -- even the most affluent among his clients, who are not as endangered by the fallout from this crisis but feel "more anger and less fear." They resent the partisanship and what they see as the indifference of Washington to way the debt wrangle hits citizens.

"People are fiddling while Rome is burning," he says.

"There's a sense of helplessness," says Dr. Stephen Josephson, a psychologist who is clinical assistant professor at Cornell University Medical School. "Most people don't have a lot of faith in politicians."

But Josephson says that just as with more personal anxieties, people might want to consider re-directing their attention away from the anxiety source that the debt crisis has become.

"The goal with any intrusive worry is to limit the amount of time you put into it," he says.

Label it and shift you attention, he suggests.

"If you pay a lot of attention to negative thoughts," he adds, "it's like with a plant -- it grows."

Gottfurcht agrees that dwelling on the problem is anxiety-producing and says people should spend more time with loved ones and avoid too much contact with those they find toxic and upsetting -- which might mean curbing excessive media exposure to some of our national leaders. He suggests activities that are proven stress-busters, like exercise, meditation, hot showers, deep breathing and listening to soothing music.

Control what you can, says Josephson, and accept the fact that you can't control the debt ceiling.

"Where is it written that everything is supposed to be hunky-dory?" he asks.

Search for